Every day, I walk from home to studio along the Thames Path. I pass housing estates, industrial buildings, parking lots and cafes, even a ferry port. Most interestingly, I pass Woolwich Dockyard, formerly a site of empire and power, now largely abandoned. Overgrown, covered in plant life and litter, surreptitiously used by foxes and birds and people, a space forgotten. Time seems to almost stand still in this spot, except that it doesn’t.

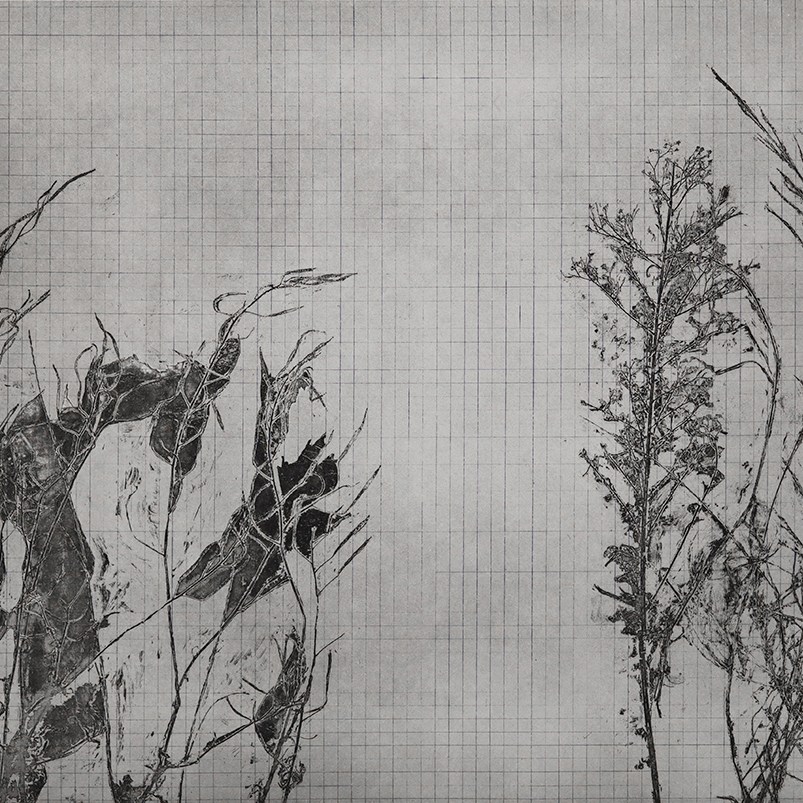

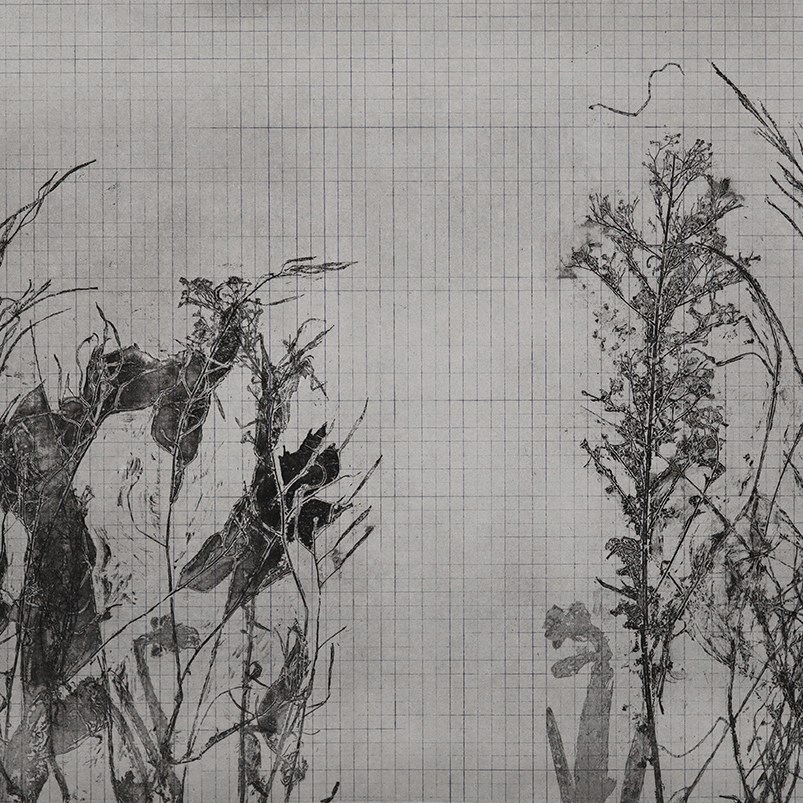

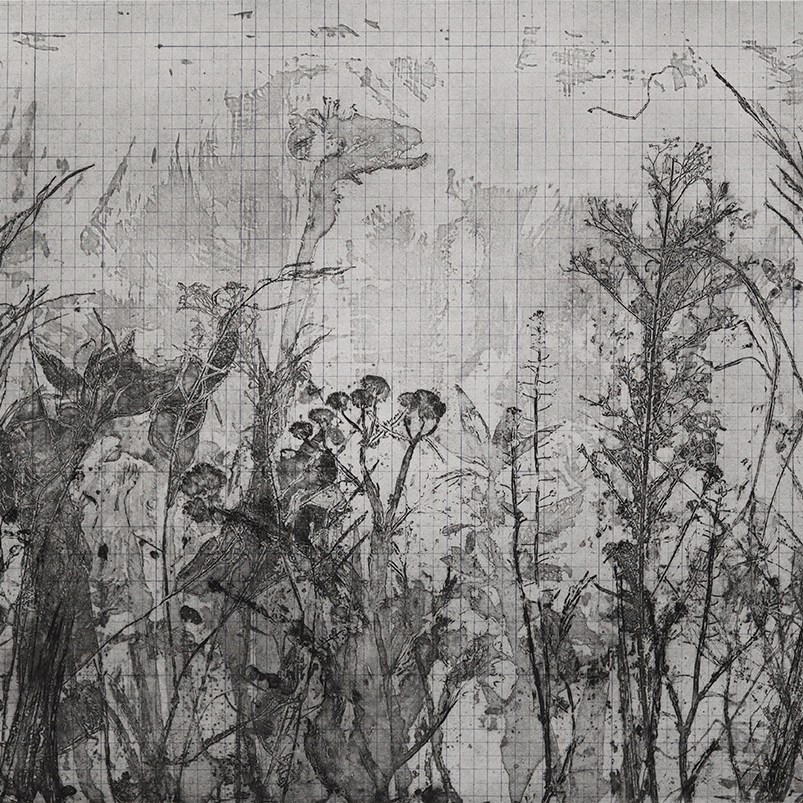

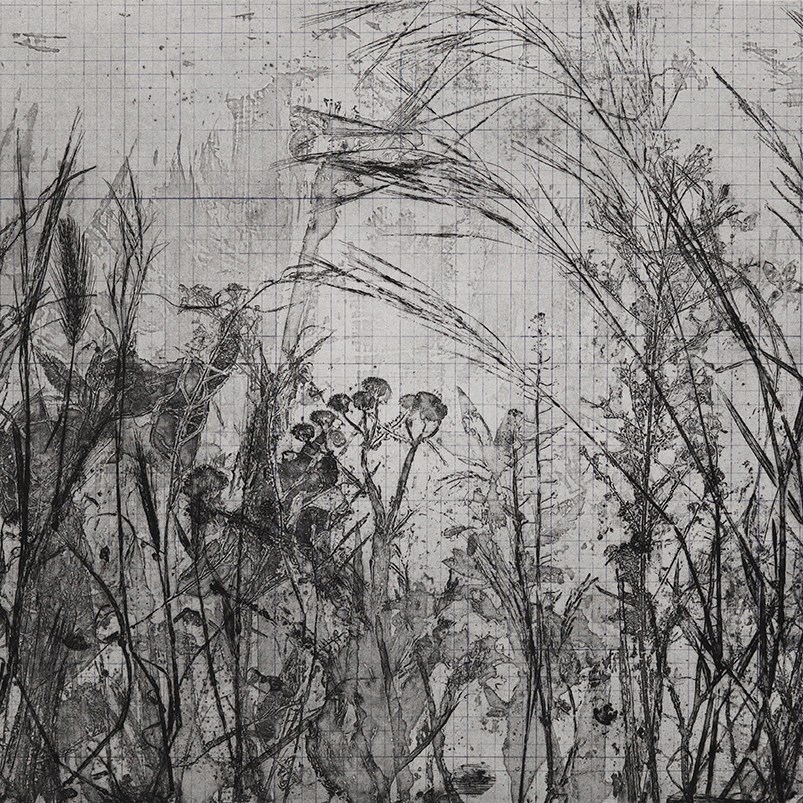

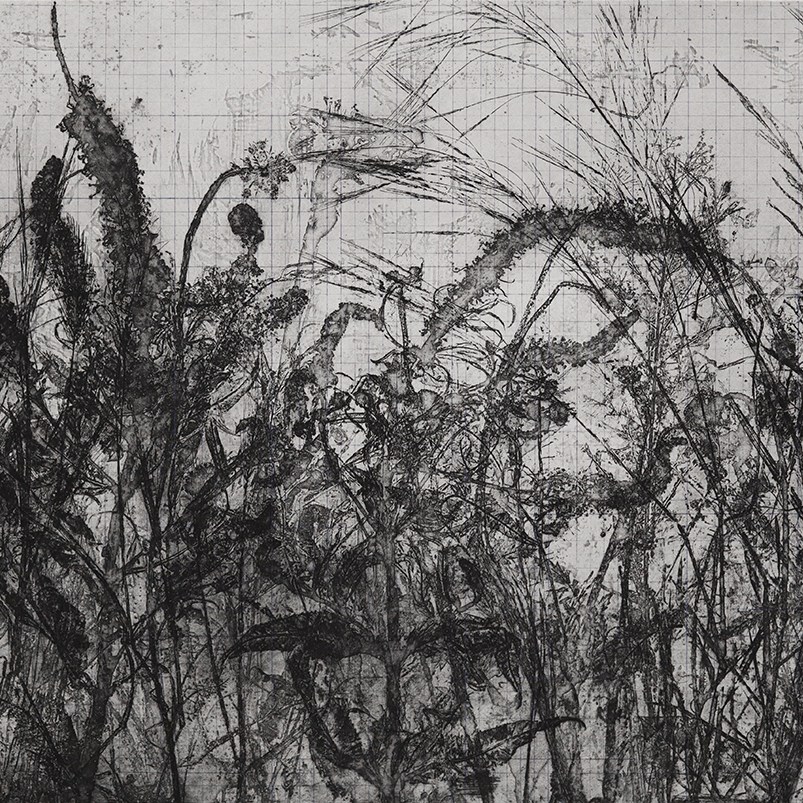

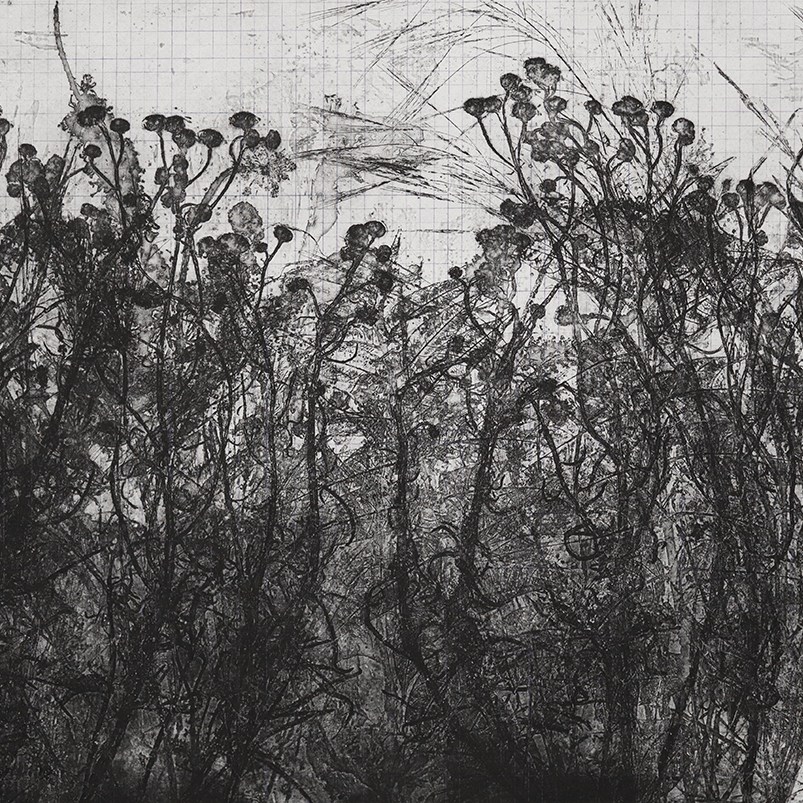

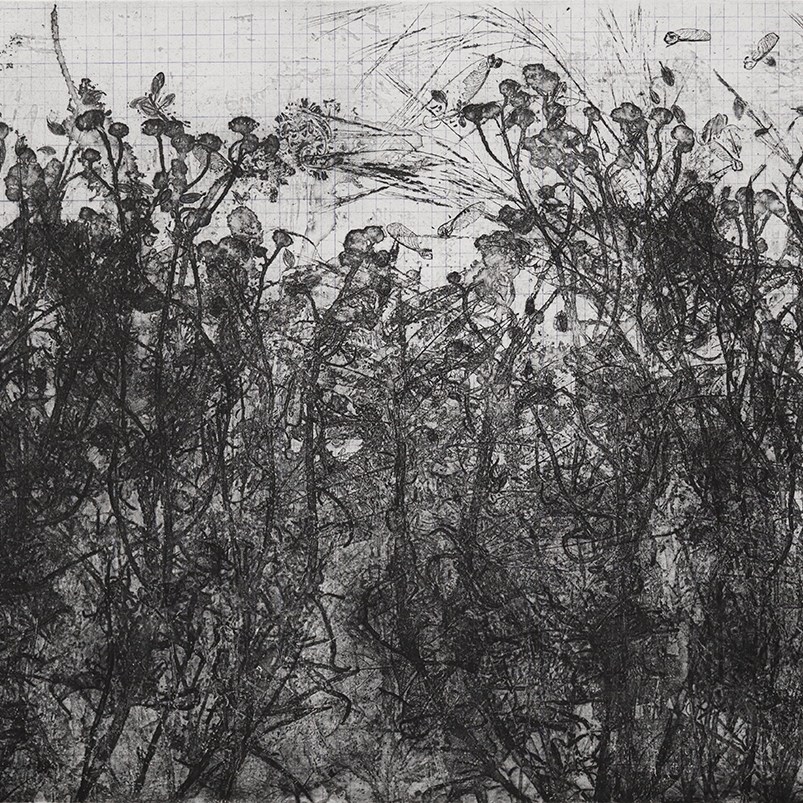

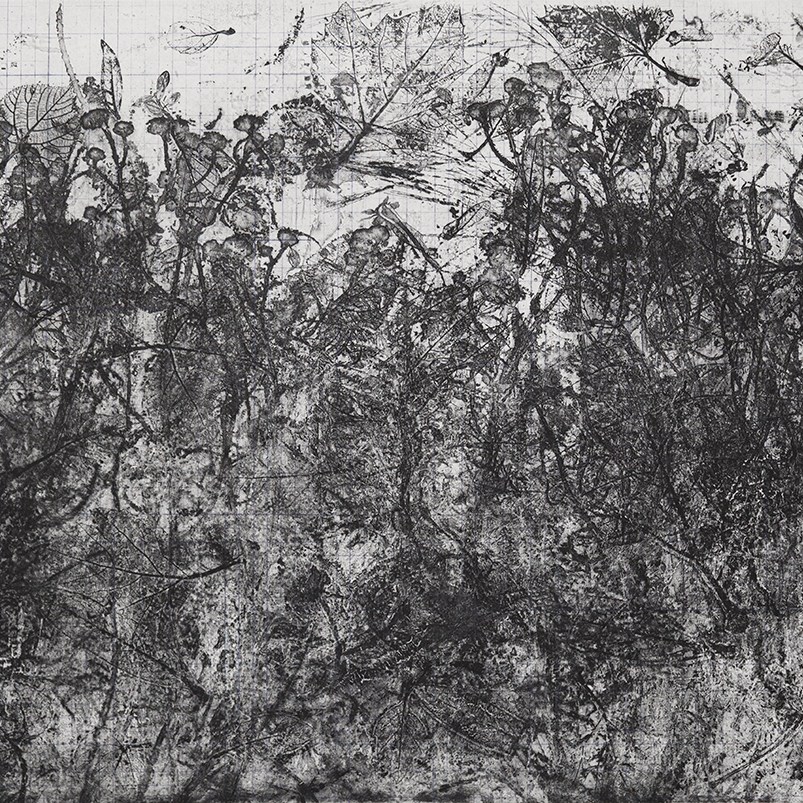

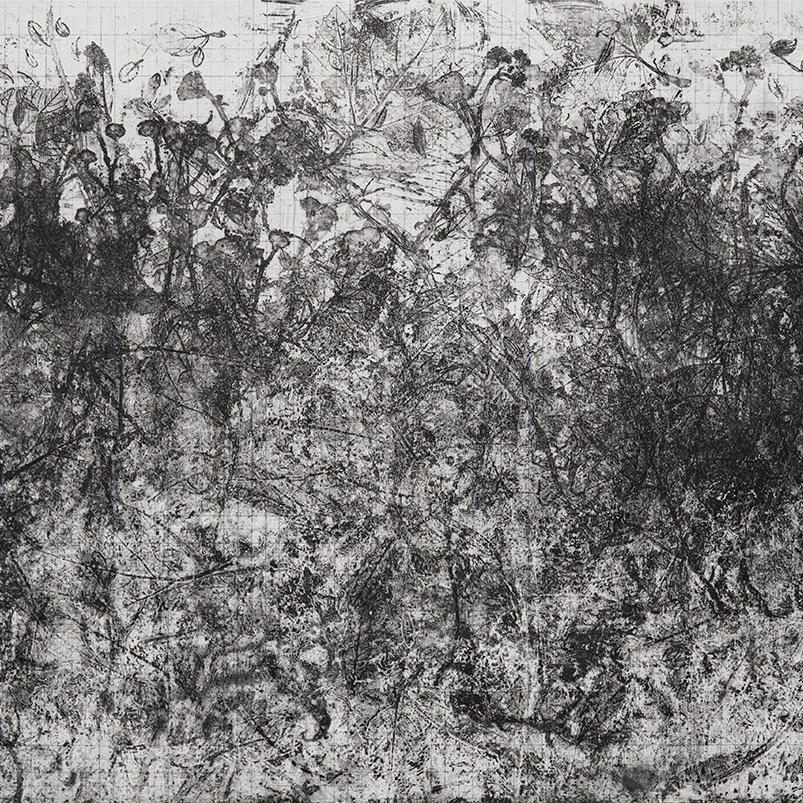

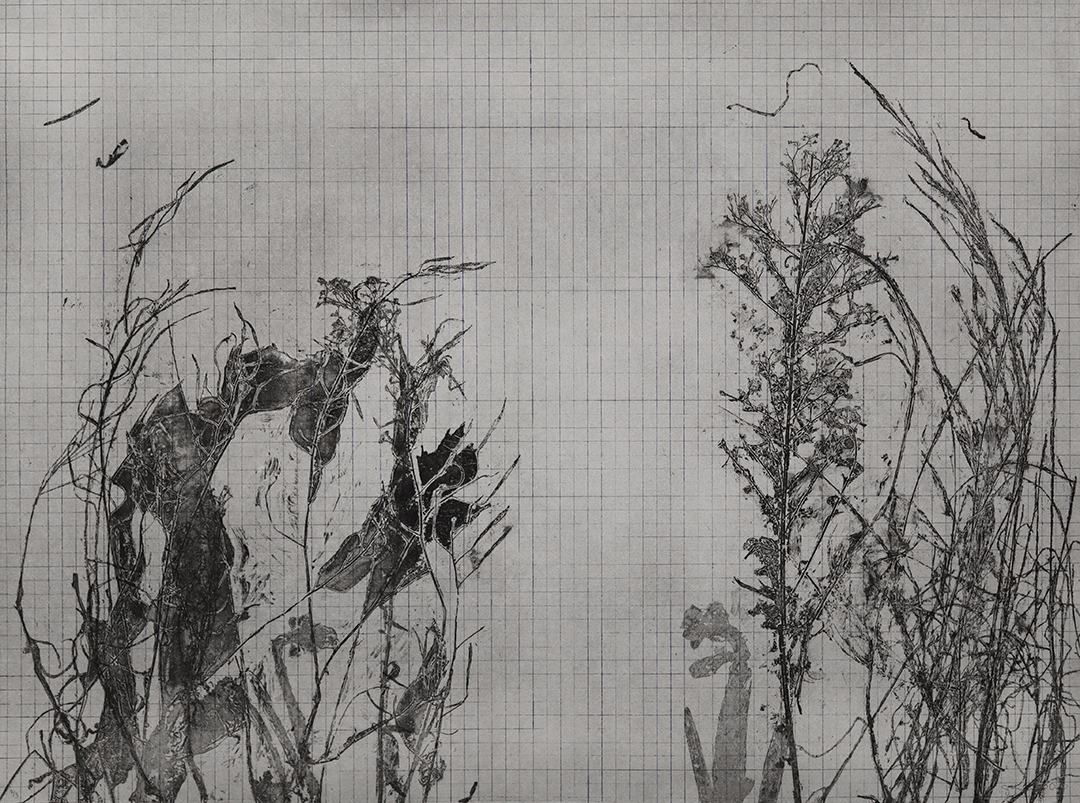

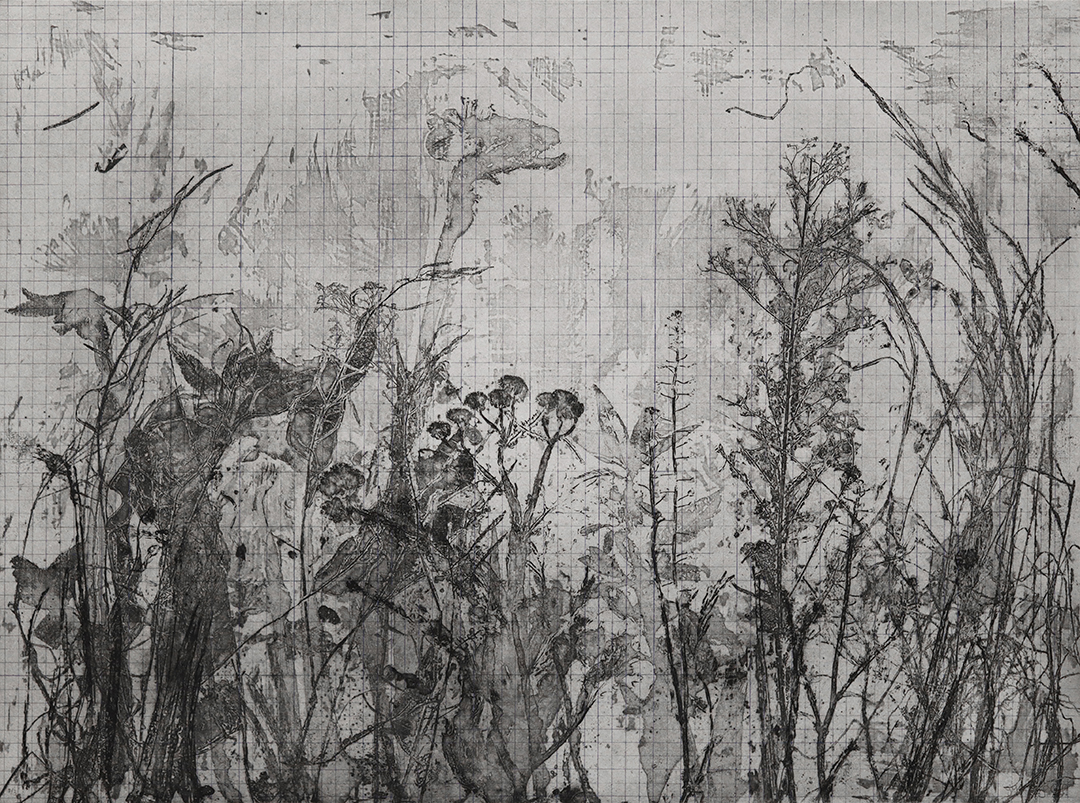

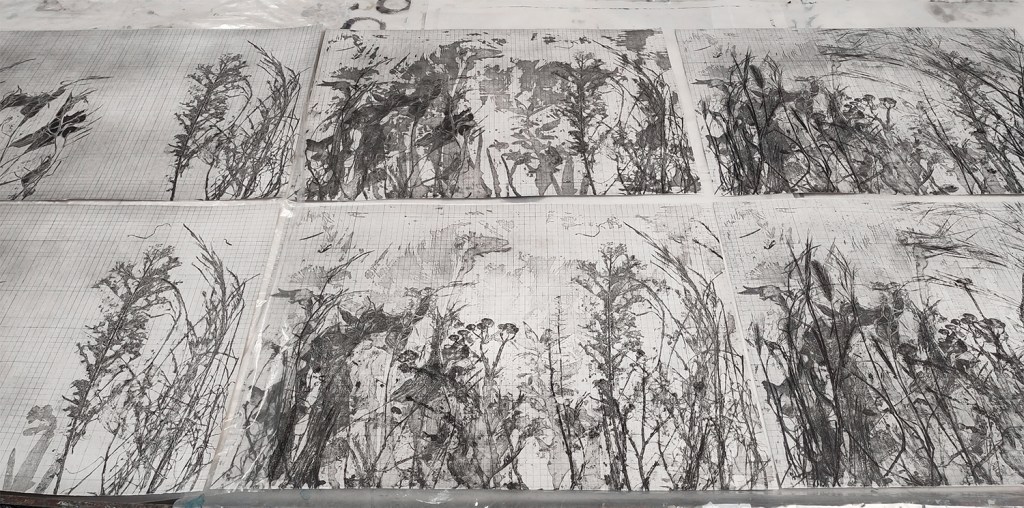

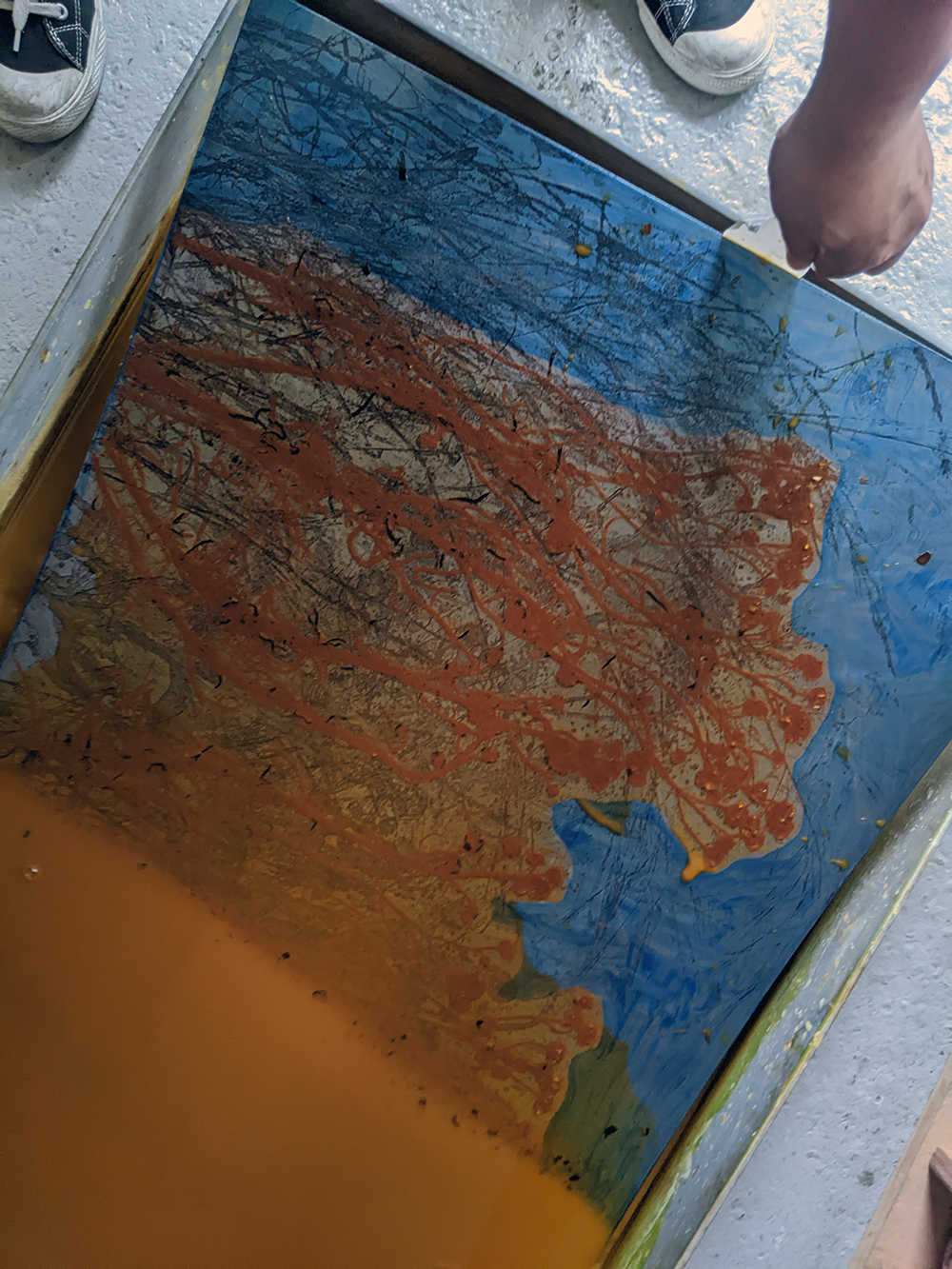

Each month, for 12 months, I foraged the area for plant life to form a series of prints showing the change and life still present in this, my small corner of the world. The harsh and baren winters give way to daffodils, wild poppies, lavender, marsh plants, propellor keys, ferns, grasses, and more. Every month, my cuttings were applied to the same plate, as the plants spring forth in the same place, overriding what came before. A single large steel plate, a diary for a year.

Printed in small editions of just 3, each entry of the diary is a window into a specific place and time. The notebook grid laid down by a separate plate, ties the series together as a sequence of observations. Instead of pen or pencil, soft ground and saline sulphate deeply etch each month as a new record onto the surface of the steel.

The Woolwich Dockyards were established in 1512 by King Henry VIII to build his ship, ‘Great Harry’, or ‘Henry by the Grace of God’. For the next four centuries, it was a site of industry. The two dockyard slips that remain are surrounded by evidence of this – gun batteries, canons, clocktowers, plaques, timber slips, iron sheds, all remain, repurposed for modern life.

As well as researching Woolwich Dockyard, and the consideration of aesthetics in making, this series was an opportunity to scale up research from the previous year on sustainable platemaking. Using lower toxicity lascaux grounds, saline sulphate mordent, solvent alternatives, and considering deeply the disposal and waste aspects of printmaking, these all added to a particular journey from past, to present, to future.

I am particularly aware of myself and my body in this work – the scale being what I could achieve unassisted, the research into safer practices a direct benefit to prolonging my work life, the research into more sustainable practices a direct benefit to prolonging printmaking’s place in the artistic canon of a world undergoing climate crisis. Working with a single plate, in particular, was important as metals having a high carbon and resource footprint. The single plate eliminates the ability to produce editions later – what I have is all that will ever be from earlier incarnations.